Table of Contents

As a tax lien investor, I’ve come to appreciate the importance of property rights in the United States.

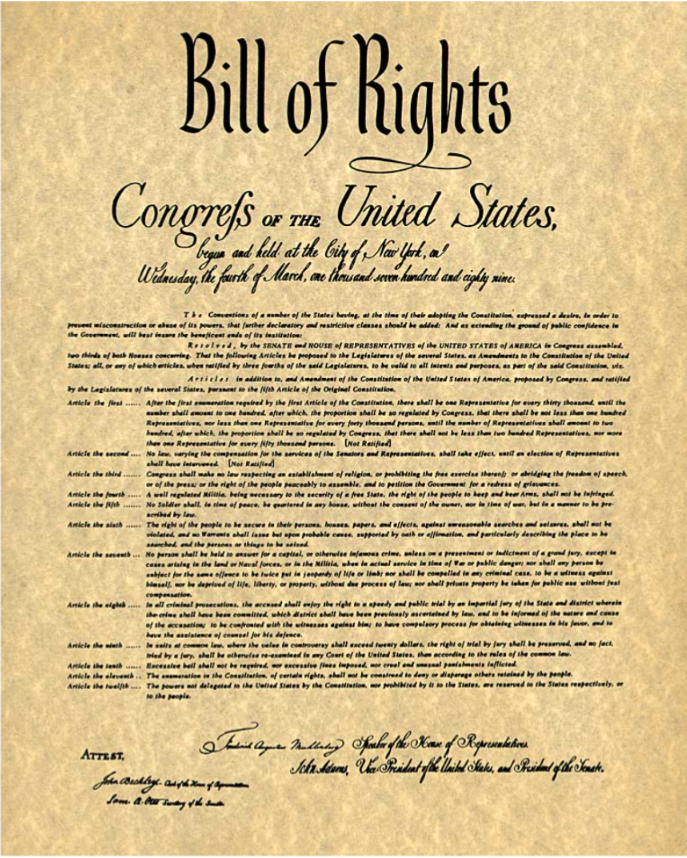

The Constitution, and specifically the Fifth Amendment, plays a crucial role in safeguarding these rights.

One of the most significant parts of the Fifth Amendment is the Takings Clause, which states that private property shall not “be taken for public use, without just compensation.”

This clause is a vital protection for property owners, ensuring that the government cannot simply seize their property without fair payment.

In this article, I’ll dive into the Takings Clause, exploring its historical context, its scope, and its implications for newer tax lien investors like myself.

I’ll also discuss some of the key Supreme Court cases that have shaped our understanding of this important constitutional provision.

By the end, you’ll have a solid grasp of the Takings Clause and how it impacts your rights as a property owner and/or investor.

Image Credit: https://blogs.shu.edu/americanhistory/2023/07/07/the-bill-of-rights/

What is the Takings Clause?

The Takings Clause is part of the Fifth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which is part of the Bill of Rights.

The clause reads: “nor shall private property be taken for public use, without just compensation.”

This simple phrase packs a lot of meaning and has been the subject of much legal interpretation over the years.

At its core, the Takings Clause is about protecting property rights. It acknowledges that the government has the power to take private property for public use, but it also requires that the government provide “just compensation” when it does so.

This ensures that property owners are not forced to bear the cost of public projects or improvements without being fairly compensated.

The Takings Clause has two key components: “public use” and “just compensation.”

The “public use” requirement means that the government can only take private property for a legitimate public purpose, such as building a road, a school, or a military base.

It cannot take property purely for private benefit.

The “just compensation” requirement means that the government must pay fair market value for the property it takes.

This is meant to put the property owner in the same financial position they would have been in if the taking had not occurred.

The origins of the Takings Clause can be traced back to English common law, which recognized that the sovereign had the power to take private property for public use, but required that compensation be paid.

This principle was carried over into American law and was included in the Bill of Rights to protect property owners from government overreach.

The Scope of the Takings Clause

The Takings Clause applies to two main types of government actions: physical takings and regulatory takings.

Physical takings are the most straightforward. They occur when the government physically seizes private property, either by claiming ownership or by occupying it.

The most common example of a physical taking is eminent domain, which is the government’s power to take private property for public use.

Regulatory takings, on the other hand, are a bit more complex. They occur when government regulations limit the use of private property to such a degree that the property loses significant value.

In some cases, a regulation can be so restrictive that it effectively amounts to a physical taking, even though the owner still retains title to the property.

The concept of regulatory takings has evolved over time through Supreme Court decisions.

In the early 20th century, the Court recognized that a regulation could go “too far” and amount to a taking.

However, it wasn’t until the 1970s and 1980s that the Court began to develop clearer tests for determining when a regulatory taking has occurred.

One of the most important of these tests is the Penn Central test, named after the landmark case Penn Central Transportation Co. v. New York City.

Under this test, courts consider three factors:

(1) The economic impact of the regulation on the property owner.

(2) The extent to which the regulation interferes with the owner’s investment-backed expectations.

(3) The character of the government action. If a regulation goes too far based on these factors, it may be considered a taking that requires compensation.

Another important test is the Nollan-Dolan test, which applies to situations where the government demands that a property owner give up something (like an easement) in exchange for a permit.

Under this test, there must be a “nexus” and “rough proportionality” between the government’s demand and the impact of the proposed development.

If these requirements are not met, the demand may be considered a taking.

Image Credit: https://www.rocketmortgage.com/learn/eminent-domain

Eminent Domain and the Takings Clause

Eminent domain is perhaps the most well-known application of the takings clause.

It is the power of the government to take private property for public use, even if the owner does not want to sell it.

Eminent domain has been used for a wide range of public projects, from building highways and airports to creating parks and preserving historic sites.

However, the use of eminent domain has also been controversial, particularly when it involves taking property from one private owner and transferring it to another private party.

The most famous case in this area is Kelo v. City of New London, decided by the Supreme Court in 2005.

In Kelo, the city of New London, Connecticut, wanted to take several private properties as part of an economic development plan.

The plan involved transferring the properties to a private developer who would build a hotel, offices, and other commercial facilities.

The property owners argued that this was not a legitimate public use under the Takings Clause.

The Supreme Court disagreed, holding that economic development can be a valid public use.

The Court reasoned that the city’s plan served a public purpose by creating jobs, increasing tax revenues, and revitalizing a distressed area.

Therefore, the use of eminent domain was constitutional, even though the properties were ultimately being transferred to a private party.

The Kelo decision was highly controversial and sparked a national debate about the limits of eminent domain.

Many states responded by passing laws that restricted the use of eminent domain for economic development purposes.

Some states went even further and passed constitutional amendments that provide greater protection for property rights.

Regulatory Takings and the Fifth Amendment

Another significant case in the area of regulatory takings is Lucas v. South Carolina Coastal Council, decided in 1992.

In Lucas, a property owner purchased two beachfront lots with the intention of building single-family homes.

However, after the purchase, the state passed a law that effectively barred the owner from building anything on the lots.

The Supreme Court held that this was a taking that required compensation.

The Court reasoned that when a regulation deprives a property owner of all economically beneficial use of their property, it is equivalent to a physical taking and requires compensation under the Fifth Amendment.

Image Credit: https://www.studocu.com/en-us/document/pace-university/property/takings-flow-chart/38183487

Just Compensation Under the Takings Clause

When the government takes private property under the Fifth Amendment, it is required to provide “just compensation” to the property owner.

The Supreme Court has interpreted this to mean that the owner must be paid fair market value for the property.

Fair market value is typically defined as the price that a willing buyer would pay a willing seller for the property, assuming that neither party is under any compulsion to buy or sell and that both parties have reasonable knowledge of the relevant facts.

Determining fair market value can be complex, particularly when the property is unique or when there are few comparable sales in the area.

In these cases, appraisers may use a variety of methods to estimate value, such as the income approach (based on the property’s potential to generate income) or the cost approach (based on the cost to rebuild the property).

When the government takes only a portion of a property, the owner is entitled to compensation not only for the part that is taken but also for any decrease in value to the remaining property.

This is known as severance damages.

Image Credit:

The Takings Clause and Property Rights Movements

The Takings Clause has been a focal point for property rights advocates who argue that government regulations have gone too far in restricting the use of private property.

These advocates believe that the government should compensate property owners not only for physical takings but also for regulatory takings that significantly diminish the value or use of their property.

The property rights movement gained momentum in the 1980s and 1990s, as concerns grew about the impact of environmental regulations on property values.

Some property owners argued that regulations aimed at protecting wetlands, endangered species, and other environmental resources effectively took their property without compensation.

In response to these concerns, some states passed laws requiring the government to compensate property owners for regulatory takings.

These laws, known as “takings bills,” typically require the government to conduct a “takings impact analysis” before implementing new regulations and to compensate owners when regulations reduce property values by a certain percentage.

However, critics argue that such laws could have a chilling effect on necessary public health and safety regulations.

They also point out that property ownership has always been subject to reasonable regulations for the common good, such as zoning laws and building codes.

The Takings Clause in the Context of Tax Lien Investing

As a tax lien investor, understanding the Takings Clause is crucial.

When a property owner fails to pay their property taxes, the government has the power to place a lien on the property and ultimately to seize and sell the property to satisfy the tax debt.

This process is known as a tax foreclosure.

While tax foreclosures are an important tool for local governments to collect delinquent taxes, they can also raise Takings Clause issues.

In particular, there have been cases where the government has seized and sold a property for a small tax debt, keeping the excess proceeds from the sale rather than returning them to the property owner.

This was the issue in a recent Supreme Court case, Tyler v. Hennepin County.

In Tyler, a 94-year-old woman’s home was seized and sold by the county due to a $15,000 tax debt.

The home sold for $40,000, but the county kept the entire amount.

The property owner argued that this amounted to an unconstitutional taking of her property.

The Supreme Court agreed, holding that the county’s actions violated the Takings Clause.

The Court reasoned that the owner had a property interest in the surplus proceeds from the sale, and that the government could not take this property without compensation.

The Tyler case highlights the importance of understanding the Takings Clause for tax lien investors.

While investing in tax liens can be a profitable strategy, it’s crucial to ensure that the government’s actions in seizing and selling properties comply with constitutional requirements.

As a fellow tax lien investor, I encourage you to stay informed about legal developments in this area.

I’m documenting my own journey in tax lien investing and sharing tips and insights along the way.

Consider subscribing to my newsletter to stay in the loop.

Criticisms and Debates Surrounding the Takings Clause

While the Takings Clause is a bedrock principle of American property law, it is not without controversy.

One of the main debates surrounds the scope of the clause and how broadly it should be interpreted.

Some advocates argue for a broad reading that would require compensation for a wide range of government actions that impact property values, from zoning changes to environmental regulations.

They believe that the government should bear the costs of these actions rather than imposing them on individual property owners.

However, critics argue that a too-broad interpretation could make it difficult for the government to enact necessary public health and safety regulations.

They point out that many government actions, such as building a new highway or school, can affect property values but are not typically considered takings requiring compensation.

Another area of controversy involves the use of eminent domain for economic development purposes.

Some argue that taking property from one private owner and transferring it to another for the sake of economic development is not a legitimate public use under the Takings Clause.

They believe it unfairly benefits private parties at the expense of individual property rights.

However, others argue that economic development can serve important public purposes, such as creating jobs and increasing tax revenues.

They believe that local governments should have the flexibility to use eminent domain as a tool for revitalizing distressed areas.

Final Thoughts

The Fifth Amendment’s Takings Clause is a crucial protection for property rights in America.

It ensures that the government cannot take private property without fair compensation, whether through physical seizure or regulatory actions that significantly diminish property values

.

As our understanding of property rights evolves, so too does the interpretation of the Takings Clause.

Landmark Supreme Court cases like Penn Central, Lucas, and Kelo have helped to define the scope of the clause and its application to different types of government actions.

For tax lien investors, understanding the Takings Clause is particularly important.

As the Tyler case illustrates, government actions in seizing and selling tax-delinquent properties must comply with constitutional requirements, including the obligation to return surplus proceeds to the property owner.

As we navigate the complex landscape of property rights and government power, ongoing legal developments and public dialogue will be essential.

The Takings Clause reminds us that the protection of individual property rights is a foundational principle of our legal system, one that must be carefully balanced with the needs of the broader community.

Whether you’re a seasoned investor or just starting to explore the world of tax liens, a solid grasp of this situation is invaluable.

By staying informed and engaged, we can all navigate the investing landscape efficiently and minimize losses by understanding all risks involved in tax lien investing and the potential outcomes.

P.S. I’m not an attorney nor do I pretend to be one on TV, please take anything stated in this article with a LARGE grain of salt these are just my observations and interpretations of the law.

BUT with that said if you are a fellow tax lien investor and you enjoy articles like this, please feel free to follow me along my tax lien investing journey by subscribing to my newsletter!

Thanks